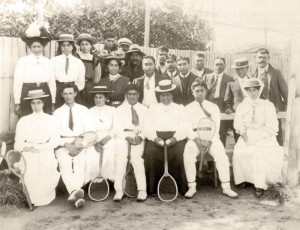

Shearers and shepherds and their whānau performing a haka prior to their weekly Sunday recreation of tennis on a grass court at the Elms Hill Station, Central Hawkes Bay in 1899.

History

The history of Maori tennis is littered with a glimmering array of people and events.

History relies on the memory of those who have created it, those who have witnessed it, those who have recorded it, those who remember it, those who have been told about it, those who have heard about it, and those who have embellished it!

That we can look back and see where we have come from: so too can we now look forward and know where we are going.

Origins

Early settlers brought the game to New Zealand during the late 1870s.

Māori quickly picked up the skills and social opportunities of the game shortly after it was introduced to the country and were soon excelling at the sport. Widespread competitions were being organised among hapū and iwi by the turn of the century.

The history of Māori tennis is one of remarkable achievement and commitment, from the early days when improvised tennis courts were carved out at marae and kāinga – to its heyday in the 1950s, when the number of Māori from iwi throughout the country taking part in Māori tournaments rivalled and even outstripped participation in Pākehā events.

Adapting and Improvising

While it is not certain in which region tennis was first played by Māori in New Zealand, it is known that Māori were playing tennis in these formative years in regions such as Hawkes Bay, Whanganui and the East Coast.

Tennis was particularly strong in the Hawkes Bay area in the late 19th century. Photographs and anecdotes reveal Māori from Ngāti Kahungunu working on large farms and sheep stations in Hawkes Bay picking up the sport in the 1890s.

One thing is certain, the game was being played to a high standard by Māori in the 1890s, and by the early 1900s the sport was established with hapū and iwi throughout the country. Tennis courts were created at many marae and were carefully maintained in prominent areas adjacent to marae buildings.

Stories abound of Māori in the early days ingeniously scraping out a surface for a court, and improvising with make-shift nets of string, flax or other materials stretched across the court. Lines would often be marked in the dirt to outline the court area. In place of wire-netting fences, manuka palings were often set up around the court.

“Racquets” were fashioned out of strips of timber, sides of wooden boxes or whatever suitable materials could be adapted. These rudimentary racquets were better known as bats.

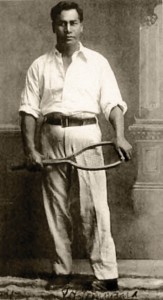

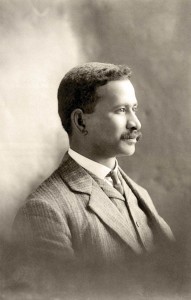

Sir Maui Pomare

In 1876, Maui was born into the cauldron of the Taranaki land wars. Not only were the people suffering confiscation and alienation of land through unjust laws and shady practices, but poverty and disease, such as typhoid and measles, contributed to the notion of a dying race.

Young Maui was sent to a boarding school, Te Aute College, in Hawkes Bay where he excelled in the classroom and was a fine all-round sportsman with a passion for tennis.

Before he graduated as a doctor in Battle Creek, Michigan, in 1899, Maui won the prestigious Inter-University Tennis Championships of the USA – a truly remarkable effort and ground-breaking achievement in both sport and academia.

As the first New Zealander to win what has been rated as the equivalent of the US Tennis Open, Dr Maui Pomare returned to New Zealand in 1900 and began a life dedicated to the salvation of his people – in medicine and later, in politics.

He was awarded a Knight Commander of the British Empire (KBE) in the Queen’s Birthday honours list in 1922 for his services to medicine and commitment to helping the Māori people.

The following year, Sir Maui Pomare was made Minister of Health.

Dress Code

While Sir Maui may not have had time for tennis on his return to New Zealand, the sport continued its rapid development. However, the very strict Victorian dress code made the standard of dress required for the sport a challenge for Māori players.

Women were required to wear long flowing skirts, and men always had to wear long trousers. Despite widespread poverty among Māori people, a lot of effort was put into ensuring the appropriate clothing was worn. Many families made sure their players were dressed in “tennis whites,” even if it meant making do with sewing uniforms from flour bags or other suitable materials.

The dress code and subscriptions to clubs were also a way of restricting the game to the well-off members of society, giving tennis the upper class reputation which has been hard to shake off in New Zealand until the early 1970s.

Inter-Marae Tennis

The strict dress code may have inadvertently contributed to the success of the game within a Māori setting. Many Māori were unable to meet the dress code required by clubs – not to mention the subscription fees. Nevertheless, they adapted to the game and adapted the game to their needs. By the early 1900s, inter-marae tennis competitions were being played in many regions. The first competitions were localised among hapū and whānau.

The benefits of this healthy pursuit were not lost on the Māori people. Māori leaders set a good example by involving themselves in the sport, either by playing or administering the game, and by encouraging their people to be active participants. As the popularity of the sport developed, so the competition was extended from inter-marae to inter-rohe competition.

Marumaru Cup

Whanganui was one of the first regions to organise a full-scale rohe competition, albeit for their own Hauauru tribes. Their first major rohe tournament was contested in Easter 1907. It was to be an annual event, played for the Marumaru Cup. The cup was named after a prominent Whanganui kaumātua, Taraua Marumaru.

By 1910, the Whanganui organisers, anxious to test themselves against other regions, invited Heretaunga to take part in the competition. The tournament was held in Palmerston North. We can’t be certain of the reaction of the Whanganui team, but they lost their taonga, the Marumaru Cup, to Heretaunga.

By virtue of Heretaunga playing Whanganui, the Marumaru Cup became an inter-rohe trophy. The competition was eventually extended to other rohe throughout the country. This inter-rohe competition was the forerunner to the National Māori Championships which we enjoy today.

Paraire Influence

Paraire Influence

Paraire Tomoana of the Heretaunga team had a huge hand in the demise of the Whanganui team in the inaugural inter-rohe Marumaru Cup Competition. Not only did he win the singles, but he also won the doubles with the Reverend T H Katene, and the mixed-doubles with Mere Houkamau Stainton. Like Paraire, Mere also won all three championship events.

In 1911 the competition was again held in Palmerston. Paraire repeated his win in the men’s championship and Ani Makitonore (Mrs Rev. Katene) won the women’s title. However, because the points system was calculated on the number of sets each team won, the taonga returned to Whanganui.

Sir Apirana Ngata

“The Father of Māori Tennis”

E tipu e rea mo ngā ra o tou ao!

Ko to ringa ki ngā rakau a te Pākehā

Hei ara mo to tinana

Ko to ngakau ki nga taonga a o tipuna Māori

Hei tikitiki mo to mahunga

A, Ko to wairua ki to Atua, nana nei ngā mea katoa.

Grow up o tender youth and fulfil the needs of your generation

With your hand master the arts of the Pākehā for your material well-being

In your heart cherish the treasures of your Māori ancestors as a plume of adornment for your head

Give your soul unto God, the author of all things.

This famous whakatauki, often referred to as “Te Tipu e Rea,” sums up Sir Apirana Ngata’s vision for Māori. He believed Māori could excel in all facets of Pākehā life, in all physical and intellectual pursuits and at the same time, honour and represent Māori culture and traditions.

Sir Apirana’s support for Māori tennis, and other sports, is a clear example of his vision in practice.

Born to Lead

If anyone was born to lead, Sir Apirana certainly was. Born on 3 July 1874 at Te Araroa on the East Coast, his birth had been eagerly anticipated. Great expectations were held for his future role in Māori society. From an early age, he was groomed for leadership in both Māori and Pākehā cultures.

His father, Paratene Ngata, Ngāti Porou, was a store keeper, a progressive farmer, a Native Land Court Assessor and an expert in tribal lore. His mother, Katerina Naki, was the daughter of an itinerant Scot, Abel Knox.

Apirana attended Te Aute College, where his political aspirations were ignited in debates with other students, including one, Maui Pomare. Students weren’t the only ones to benefit from the astute mind of Apirana. He debated with, and was encouraged by his teachers.

He was one of the earliest Māori university scholars, indeed the first Māori to graduate from a university, and one of the first of any race to gain a BA (Canterbury 1893) and a LLB (1897) in this country.

At the time of the 1926 Māori Championships in Rotorua, Sir Apirana, at the age of 51, had been in Parliament for 24 years. His main portfolio being that of Minister of Native Affairs. He had considerable experience in implementing policy.

The idea of formalising Māori tennis into a constituted national organisation fitted his philosophy of using the tools of the Pākehā. He believed that Māori, could align themselves with their Pākehā counterparts and operate within a prescribed framework, while at the same time, continue under their own terms.

New Zealand Māori Lawn Tennis Association

New Zealand Māori Lawn Tennis Association

Sir Apirana’s great friends, Tai Mitchell, Pei Te Hurinui Jones and Tukere Te Anga, were instrumental in assisting him to write a constitution, thus forming the inaugural New Zealand Māori Lawn Tennis Association (NZMLTA) during the Māori Championships, Easter 1926, in Rotorua.

The 1926 inaugural national tournament in Rotorua was the first contest in which all the districts sent their best players. Elimination rounds were held earlier in each district so only the best players attended the tournament. Despite the elimination rounds, there was an impressive 94 players in the men’s singles event at the 1926 event.

NZMLTA in Whanganui

In 1927, the second NZMLTA Championships was held over the Easter weekend at Putiki in Whanganui. Sir Apirana, while clear that an autonomous Māori tennis organisation was important, also wished the NZMLTA to work in harmony with the Pākehā tennis organisations. He ensured Pākehā dignitaries were given a prominent role in the proceedings, including the president of the Whanganui Lawn Tennis Association Mr G H Pownall and the Mayor of Whanganui, Mr W A Veitch.

1927 Whanganui (Putiki), NZMLTA Committee – President Tukere Te Anga seated (centre), far left Pei Te Hurinui Jones (seated).

Pei Te Hurinui Jones – Secretary NZMLTA and King Koroki Te Rata Mahuta Tawhiao Potatau Te Wherowhero – Patron NZMLTA.

Pei Te Hurinui Jones

During that same year, 1927, Pei was instrumental in hosting a remarkable tennis event: a New Zealand Māori Tennis Team played against a touring British Isles Team in Whanganui.

Pei was the inaugural winner of the NZMLTA Championship Men’s Singles in 1926. In addition to his many other duties – translating, writing, heading various Māori organisations, and working in the boardrooms and courts dealing with land issues – Pei was also a key advisor to King Koroki, Princess Te Puea and later, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu.

Patron

While there is no evidence to suggest that Pei was the instigator in the inauguration of King Koroki as patron of the NZMLTA in 1947, we can only surmise that Pei was responsible for this wonderful outcome.

Pei’s influence may also be attributed to two other patrons, that of Princess Te Puea in 1949, and Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu in 1975.

Apirana’s Passing

The AGM in 1951 acknowledged the death of Sir Apirana Ngata at the age of 76. The nation had lost a champion of Māori land retention and development, a politician, a leader, a scholar, a writer, a tennis aspirant and – as legend would have it – “the father of Māori tennis.”

Affiliation with NZLTA

Since its inception, the New Zealand Māori Lawn Tennis Association has been affiliated with the New Zealand Lawn Tennis Association.

At the NZMLTA AGM’s, two committee members were elected each year as delegates to attend NZLTA meetings.

This historical extract was adapted from the chapter on “Origins” in the book, “A History of Maori Tennis” published by AMTA, 2006.